It was a sunny afternoon at Green Lake Park in Seattle. August 6, 2025, marks the eightieth anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, the first of two nuclear bombs dropped on Japan before the Second World War came to an end on August 15, 1945. These two nuclear bombs killed thousands instantly, and many who survived the initial blast had to deal with both acute and long-term effects from the radioactive fallout.

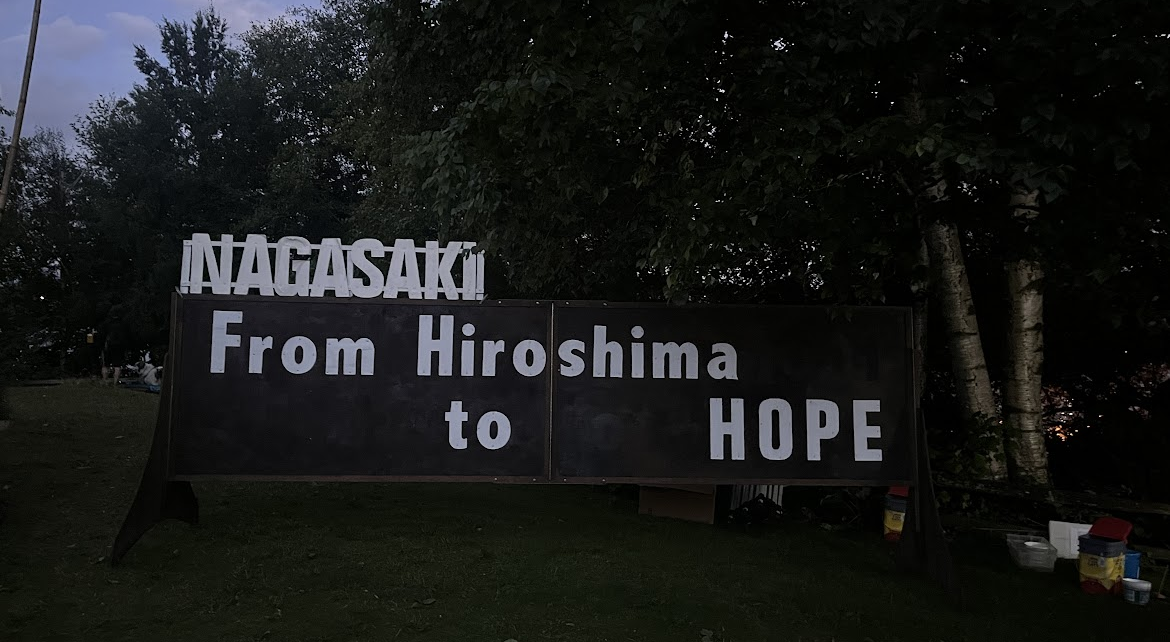

Commemorations for the bombing of both Hiroshima and Nagasaki occur throughout the world. One of the largest events outside of Japan, called From Hiroshima to Hope, took place at Green Lake.

History:

The first From Hiroshima to Hope event was held in 1984, and is hosted by a committee who direct and sustain it. As a nonprofit organization, the entire event is organized and supported by volunteers. The first event, co-organized by the Japanese American Civil Liberties Seattle Chapter and Washington Physicians for Social Responsibility, took place in a church with almost 300 attendees. Soon after the first event, a board member was inspired by a commemoration event in Wisconsin, and introduced the Lantern Ceremony. They integrated the idea into the program and it has since become a staple of the event.

The event has grown larger each year, with more sponsors and participating organizations involved. Although the event began as a commemoration to honor the victims in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the scope of From Hiroshima to Hope has expanded to oppose violence at all levels. As strong advocates for peace, the organizers have commemorated other groups and causes, using their event to promote a broader vision of peace. For example, when a Sikh man was murdered after 9/11, From Hiroshima to Hope included the Sikh community in the event and floated lanterns inscribed in Punjabi. In the aftermath of the Columbine shooting, the organizers focused on “youth peacemaking,” creating a program that centered on youth voices and how they view peace.

From Hiroshima (And Nagasaki):

With many businesses, restaurants, and the Woodland Park Zoo in the surrounding area, Green Lake is a popular location in Seattle. The park and three mile lake trail loop become hot spots during the summer months. August 6 was no different, packed to the brim with Seattleites. As I walked with my friends to the ceremony, I was expecting to see the event tucked away in a corner—to my surprise, the trail ran right through the event. On the right side of the trail was tabling for numerous anti-nuclear, anti-war, and activist groups, including organizations such as Veterans for Peace, Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action, Washington Physicians for Social Responsibility, Back from the Brink, and Hanford Challenge. The other side of the trail was populated by a stage, space for seating, and the many lanterns without their covers.

The left side of the stage housed a small exhibit of photos from the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Joining the stage were two art pieces, one of which was made from a nuclear reactor blade, taken from the unfinished Satsop Nuclear Plant in Washington. This blade was made by the arts initiative, Blades for Change, which breathes new life into unused reactor blades by using them in transformative artwork—shifting their purpose from nuclear fan blades to peace-promoting art pieces. The blade on display was made by the Japanese American local artist Lauren Iida and the Wanapum/Yakama artist Johnny Buck, a recent University of Washington (UW) masters graduate and member of Students for Nuclear Justice at UW. Titled “The Wild Rose of Hiroshima,” the blade depicts folded cranes, honoring Sadako Sasaki—a Japanese girl who contracted leukemia following the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and who folded hundreds of paper cranes while in the hospital—and the wild rose, a Wanapum land plant that represents protection and cleansing. The second piece featured Yukiyo Kawano’s “Little Boy (folded).” She used kimono fabric, along with strands of her hair, to create a suspended sculpture of Little Boy, the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

As I approached the event, I was immediately exposed to pictures from the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Placed near the tabling organizations, these large pictures greeted you as you entered the event. Some images showed the destruction of the cities, others the victims, many with fatal injuries; all showed the devastation and trauma from that day 80 years ago. These challenging images serve as an important reminder. When learning about the end of the second World War, we often only hear about the bombings in passing. These photos tell us the other part of the story: the sheer devastation and the thousands of lives lost.

Across from these photos was a small exhibit with additional pictures and captions further describing the horrors and devastation. Some images showed Hiroshima and Nagasaki before and after the bombings, while others depicted victims who left only shadows.

These uncomfortable images frame the ceremony in an important way, providing necessary context and giving attendees a common starting place for the ceremony. By sectioning off a piece of the Green Lake trail loop, everyone is given an unavoidable reminder of the anniversary.

One of the speeches at this year’s event was by Norimitsu Tosu, a hibakusha (survivor of the atomic bombings), who was only three years old and survived because he was inside his house at the time of the bombing. Four of his siblings, his dogs, and his relatives were killed, and his home was destroyed. During his speech, he repeatedly cried, “Give our ___ back!” referring to something or someone that was taken that day. He continued, proclaiming, “No more Nagasaki, Hiroshima, Marshall Islands…no more war, no more.” His words affirm the hope for change: no more nuclear weapons and ultimately no more war.

To Hope:

There was a striking contrast between the bleak photos from Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the celebration of life and hope occurring at the event. People of all backgrounds were there—families, teens, children, young adults, and elders—sitting together to watch the program, and gathering on a Wednesday evening to honor the victims and celebrate hope.

After looking at the photos on the trail and in the small exhibit, I went to gather the base of a lantern for the closing lantern floating ceremony. Volunteers were writing Japanese characters for words such as commemoration, courage, bond, to love, mercy and peace, onto pieces of paper used as the outer shell of the lantern. I decided on a sleeve with the Japanese characters for hope, wanting to feel hopeful in a time when it is very easy to be pessimistic about the world. After all, change first happens with hope that things are able to change.

Having arrived early, I had ample time to explore while the performers got ready. The tabling across from the stage was a great reminder that the work for peace and nuclear justice is ongoing, with grass roots activism at its core. Being right on the trail has its benefits—on this hot August day, the constant stream of people around the lake gives ample opportunities for passersby to learn and join the conversation.

Everyone needs to start somewhere. My introduction to the nuclear realm was through an anthropology class at UW, “Surfacing the Stories of Hanford: Local and Global Health Disparities,” taught by professor Holly Barker. Although I was born and raised in Washington state, I never learned much about the Hanford Site in school. Nuclear issues are often shrouded in secrecy due to their dangerous nature, leading to limited public knowledge and making it difficult to understand their impact on our lives. In that class I learned about the Kitsap Naval Base in Bangor, which holds many nuclear submarines, making the Seattle area a potential target of nuclear attack. I additionally learned about the University of Washington’s role in the atomic program and studying the impacts of nuclear weapons. Having these tables provides an entry point for new activists to engage with nuclear justice and peace movements in Seattle.

After exploring the tables, my friends and I made our way to the stage, drawn in by the sounds of the koto played by the performer Koto no WA. It gently brought attention to the stage, setting a somber but energetic tone for the evening. After their first song, the Heron Dancers joined them, dancing and performing alongside the musicians. One of the dancers held up a large sign that read, “Never Again Means Never!”

To officially start the event, the emcee, activist Sharon Maeda, welcomed the crowd, explaining the event’s over forty-year history at Green Lake and reminding the audience that it is entirely volunteer-run. After her welcoming speech, the Seattle Kokon Taiko group performed their expressive and rhythmic pieces on the taiko drums, filling the event with an energy and a collective pulse. The keynote speaker, activist Stan Shikuma, followed with a powerful speech. He began with addressing the current state of nuclear weapons around the world, explaining that the very presence of nuclear weapons keeps us as close to nuclear war as ever. He continued by explaining that “peace is not the absence of war,” emphasizing that peace and justice must come together. Belief in hope, diversity, equity, inclusion, respect for all people, and that change can truly happen is crucial. In closing, Stan challenged the audience to do more for peace. One person can’t change the world, but if each of us make small changes, together we can.

Next up was music by The Rhapsody Songsters, a youth ensemble that focuses on the cultural heritage of its performers, celebrating the diversity of this country and the power of connecting to one’s heritage through music. Janae Lu, a Seattle Youth Poet Laureate, recited a poem about expectations and the desire for change as a young woman. The evening closed with a cello performance by Melanie Grad from the Japan-Seattle Suzuki Institute, which trains students in music. The work for peace and nuclear justice must eventually be passed on, yet many of these organizations struggle with mobilizing younger populations. By providing spaces for youth performances, the event gives young people hope that our voices matter in shaping the world we will inherit.

The final part of the commemoration was the lantern floating ceremony. With my lantern in hand and hope on my sleeve, we joined the lantern procession, led by Buddhist Monks Senji Kanaeda and Gilberto Perez, who were part of an interfaith peace walk from Salem, Oregon. The trek required walking 11 to 16 miles per day, serving as a reminder that through small steps, we can conquer big distances. The peace walk participants proceeded, followed by the emcee, the Hibakusha, speakers, performers, elders, and finally us at the tail end. My friends and I decided to stay back and wait for the crowd to clear, and I am glad we did. The view from the back was surreal as hundreds of participants gathered, making it take nearly half an hour to reach the pier. The lantern ceremony began at 9p.m., and by the time we arrived, dusk had set in and the lanterns were glowing.

Before leading the procession, the monks explained the significance of the lantern ceremony. The lantern floating ceremony is celebrated throughout Japan and the world to commemorate Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It is based on a traditional Buddhist custom called Toro Nagishi, in which lanterns honor the dead and offer prayers for the dead and peace. From Hiroshima to Hope emphasized that their ceremony honors all who have died in a violent conflict anywhere, hoping that peace can one day be found and highlighting that everyone must contribute.

Saying “never again” requires us to reject more than nuclear weapons but war itself. It calls for recognizing current conflicts and wars—in Palestine, Ukraine, Myanmar, Sudan, Yemen, and others—the role of the United States, the power of grass roots activism, and the intersectionality of these issues. Many things are out of our control, but with collective participation in making the world a safer place, change is possible. As we made our way to the pier, we handed our lanterns to volunteers wading in the water. Standing there, we watched our lanterns join hundreds of others peacefully floating across the lake.