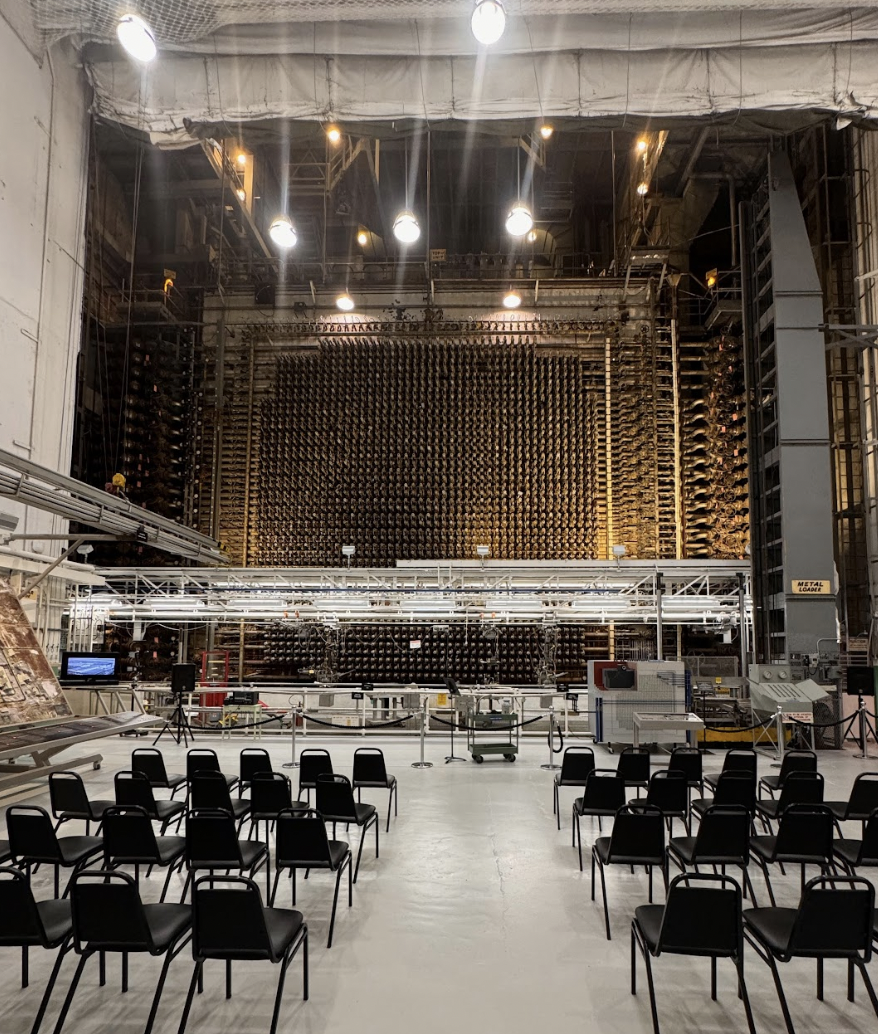

On Sept. 27, 2024, I participated in a tour, organized by the Department of Energy, of the Hanford Site’s B-Reactor, the world’s first plutonium production reactor of this scale. The tour group met at the Hanford Visitor Center in Richland, WA, and traveled by bus to the Hanford Site. Our tour guide was a nuclear engineer who formerly managed one of the reactors at the Hanford Site. When he introduced himself, he said that he had only been part of the plutonium production at Hanford for a few years, before spending the rest of his career managing the cleanup of the site, which is still ongoing. But his presentation focused on the history of scientific discoveries related to nuclear energy, such as the discovery of nuclear fission that led to the wartime construction of the B-Reactor and the production of plutonium used in the Trinity Test in New Mexico on July 16, 1945, as well as the bombing of Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. As I listened to his presentation, which was designed to convey the excitement of these scientific discoveries as well as the speed with which the large nuclear reactor was built and plutonium production began, I could not help but think of the devastation caused by the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki using plutonium produced at the reactor I was sitting in front of, and the long-lasting health effects suffered by the survivors. I had also learned about the extent of the environmental, health, and cultural impacts of the Hanford Site on the tribal communities on whose land the Hanford Site, one of the most toxic sites in the world, is located. None of these humanitarian impacts of nuclear weapons development were discussed during the presentation, except for a brief reference to the careless and casual ways in which cooling water and nuclear waste from plutonium production were dumped into the Columbia River (and its tributaries) and into the soil in the area during the early years of operation, which left me deeply troubled.

City council resolutions passed in various Northwest cities in recent years all specifically mention the Hanford Site and its far-reaching environmental and health impacts on the region. Many of the resolutions passed in Oregon cities were the result of an inspired collaborative effort coordinated by Kelly Campbell, former executive director of Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility (https://www.oregonpsr.org/) and current policy director for Columbia Riverkeeper (https://www.columbiariverkeeper.org/). In her conversation with me in August 2024, for example, Campbell told me how she drafted the resolution passed in Portland with a member of a tribal nation dedicated to protecting the natural resources of the Columbia River, a descendant of atomic bomb survivors, and Linda Richards, an expert on nuclear justice issues at Oregon State University (whose work we featured in the blog post we published last month-https://mappingnuclearlegacies.com/nuclear-waste-scholar-series-making-the-unseen-visible/), as well as local peace activists and city council members, to “make sure the language was appropriate.” Campbell noted that the goal of this collaborative work was not simply to pass a resolution, but “to build those connections… and to continue to work together.” Campbell and her colleagues wanted to make sure that these resolutions “reflect[ed] the people in the community and their experiences.” They also made sure that at hearings in the Oregon State Legislature and at city council meetings, people from affected communities testified first, before veteran anti-nuclear activists. I find the consultative and relational approach taken in Portland to be exemplary, and a model for other local efforts to address nuclear weapons development and its far-reaching impacts. This approach could be further developed in future efforts if people from affected communities take the lead in engaging local governments in these issues.

As Nalani Saito and I have argued in our article, “City Diplomacy and Nuclear Policy” (https://mappingnuclearlegacies.com/city-diplomacy/), these resolutions adopted by various U.S. city councils serve as official records of formal recognition of the health, environmental, and cultural impacts of U.S. nuclear weapons development. Local governments, such as cities, counties, and states, do not have direct jurisdiction over national nuclear policy. However, the impacts of nuclear weapons development are as local as they are national and international, and some U.S. municipalities are now actively recognizing the breadth and depth of these impacts in these resolutions. While these resolutions are non-binding and largely symbolic local actions, the power of such official recognition and acknowledgement cannot be underestimated. I continue to meet people who are unfamiliar with, and surprised to learn about, nuclear legacies that exist in the U.S. As this project has consistently sought to highlight, these legacies — and the enormous sacrifices that have been made for national security interests — include the environmental, health, psychological, and cultural impacts that have affected downwinders, atomic bomb survivors, tribal nations, Marshall Islanders, and other minoritized communities across the country. The project will continue to bring their voices, experiences, and perspectives to the call to action—to remember nuclear legacies, to recognize their pervasive presence across the country, and to prevent future and further harm from nuclear weapons.